A soldier tests the ENVG-B and Family of Weapon Sights – Individual in 2019. (Chris Bridson / Army)

ALBUQUERQUE: Increasingly miniaturized sensors and displays mean every rifleman may have a network between their sight and their binoculars.

The Enhanced Night Vision Goggles – Binocular (ENVG-B) look almost analog, like a set of fancy, lightweight binoculars mounted on a helmet. (By contrast, traditional night vision goggles are monocular, which limits depth perception). But inside, they are a sophisticated set of sensors, aided by cameras and on-board memory, that incorporate with other networked gear carried into battle.

ENVG-B is still being fielded across the force, but the Army is already developing a next-gen system, a set of augmented reality targeting goggles — a militarized Microsoft HoloLens — known as IVAS. The Army’s also developing an Adaptive Squad Architecture to ensure all the different technologies going on a soldier’s body are compatible.

“ENVG-B is a system of systems,” Lynn Bollengier of L3Harris Technologies said at this week’s annual Association of the US Army conference. These systems include integrated augmented reality aspects from the Nett Warrior tablet, as well as wireless interconnectivity with weapon sights.

Combined, that means a soldier wearing the ENVG-B can look through their binoculars, turn on the camera in their rifle’s sight, and point that sight around a corner to see and shoot, without exposing anything more than their hands or the rifle.

These kinds of technologies constitute “a defense Internet of Things,” said Vern Boyle, VP for advanced capabilities at Northrop Grumman.

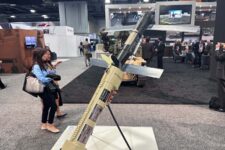

One example of this on display at AUSA was a picture-in-picture display. While still allowing the soldier 40 degrees of horizontal and vertical visibility, the ENVG-B binoculars could incorporate a small, picture-in-picture image from a second source.

ENVG-B with picture in picture capability (L3Harris)

“Any info that can make it to a tactical radio, as long as that’s in Nett Warrior, can be populated into the picture-in-picture mode in the video,” said Bollengier.

The most immediate uses of this feature would be live video from other cameras on the battlefield, including those carried by planes, drones, or other sensor-rich vehicles. Another possibility is that a soldier could upload a complete 3D model of the hill they are fighting around, drawn from the Army’s One World Terrain database.

While originally designed for training, One World Terrain is designed to be a comprehensive 3D map of the entire world, shared in a common library that can be adapted to training or battlefield needs. But bringing the 3D model into combat will require some degree of forethought, given the limitations of transferring large file sizes at a moment’s notice.

“There is no silver bullet” for transferring the 3D map files, said Ryan McAlinden, a technology advisor at Army Futures Command. Sometimes the network will have the capacity, other times getting the map might mean physically delivering a hard drive to the forward location and uploading it from there. That said, “compression has come a long way, and the maps can send over cellular networks.”

So long as the soldier in the field is capable of receiving data, there will be no shortage of ways to incorporate that information into how they fight. The primary challenge will be maintaining that connectivity and making sense of the information as it arrives.